Yardley since the war

Bomb damage was widespread during the war. In terraced streets destroyed houses have usually been restored, but there have been many rebuildings of group and single houses in modern styles. These have added to the jumble which is Yardley today, and which this essay's brief summaries have necessarily simplified. On the largest bomb-site, at the north end of Stoney Lane, two acres of crowded terraces have been replaced by multi-storey flats and maisonettes. The most obvious additions to the urban scene in the early postwar years were pre-fabs, of which only one row on Wake Green Road now survives. They were built on more than a score of sites in Yardley, on park edges and in off-street precincts. Where necessary, access streets were made - e.g. Brookwood Avenue, Braceby Grove, Sunfield Grove. Pre-fabs were built on the site of Field House Farm.

Factory development and rebuilding continued during and after the war. Apart from infilling of the Hay Mills/Tyseley area, there was the spectacular growth of the former Lucas Works off Spring Road. With other factories this came to fill a wedge between Cateswell Road and the railway line to Stratford. New industrial districts were at Kitts Green, and Broomfield Hall (between the Grand Union Canal and Woodcock Lane North, replaced by housing from the 1980s onwards). The few inter-war factories off Seeleys Road have gone or been incorporated into a new estate which filled most of the former flood-meadows between Spark and Cole. The Aldis Works on Sarehole Road were enlarged before being replaced by housing in the 1980s. There are still small factories on Yardley Wood Road at Warstock and Prince of Wales Lane. The Waterloo Brickworks continued until the 1970s, using open-cast methods around its great pit, but the Burbury works have been razed and the pit was filled for Lucas extensions. Since the 1970s, as manufacturing in general has declines, most large concerns have gone, and parts of former industrial areas have become devoted to service and even retail.

The Greenstead estate at Springfield was the last of the pre-war style council estates, in the late 1930s. Multi-storey flat blocks first appeared on the west edge of Billesley Common, on Alfred Road, and by the Yew Tree junction. In marked contrast to the pre-war building, there has been the greatest variation in type, size, height, and materials, with every sort of dwelling from bungalows to towers. Building is at higher density, gardens are small or lacking, and garages are being provided for new and older homes where possible. The absence of garages in older estates has created problems: grass verges have been ruined, and on-street parking means danger for playing children and through traffic. In recent years Yardley village has been enlarged at last, but the three-storey home for old people (closed at the end of the century and replaced by more sympathetic buildings beyond the church), and the low terraces and bungalows off Stoney Lane, do not compete with the church tower.

Probably the most remarkable feature of Yardley from the 1960s, though not the most apparent, has been the development of hidden sites. This has been carried out both by the Corporation and private builders, and is additional to the demolition of old houses such as Coldbath and Paradise Farms, and Acocks Green House, to permit high-density building in their grounds. On dozens of sites, unused land, paddocks, former allotments, etc., new streets and precincts of towers, maisonettes, bungalows and terraces, with garage rows, have been erected. Examples of these developments were the Swanshurst Lane Estate in Great Meadow on Coldbath Brook, Coldbath Farm, and the Fox Hollies towers and Bordesley Green East estates. Private estates are generally smaller but more numerous. The Coldbath estate on Yardley Wood Road covers the site of Lady Mill: this involved use of private land (a little-used part of Moseley golf course). Access to some of the new private estates is often obtained by the razing of one or two houses in enclosing streets. Factories like the Robin Hood Works (Newey Goodman later), and the former Electricars works on Webb Lane have also given way to housing. Some 'system-built' inter-war estates, e.g. at Stockfield and Gospel Lane have had to be replaced as a result of structural defects. The density of building would horrify pre-war planners: as this infilling continues it becomes clear that land was wasted in the past, but equally clear that before long there will be no unused land - and such is the pressure of population that some designated amenity areas have not been safe: an example is the over-building by the Corporation of Church Field and Stich Meadow. This former public recreation ground disappeared under new streets, towers and terraces in the late 1960s. A part of Stichford Field beside Bordesley Green East, formerly allotments, was also privately laid out in terraces of 'mews-type' houses. The dwindling number of open spaces must be in ever-increasing danger, especially since 'high rise' building has lost favour and the alternative requires more land. In addition it seems certain that whole neighbourhoods of middle-class houses with large gardens will be cleared for high-density development long before they need renewal. Planes overfly areas like Hall Green and leaflet householders, inviting them to get rid of part of their high-maintenance land in exchange for large sums of money.

A new shopping centre, public house, and municipal baths at Stechford brought modernity to the suburb's east edge. Glebe Farm has its churches and community centre, and Lea Hall shopping centre was completed. Both have libraries: Lea Hall is served by a small library in premises at the Poolway shopping precinct. This ambitious structure, built round a traffic-free square, has a large car-park. But it is cut off despite the footbridge later provided from half its customers by the dual carriageway Meadway, which continues the route from Bordesley Green to Tile Cross. Behind the great blocks of flats which border it is Kents Moat Park: the ancient Pool Road, the Yardley-Sheldon boundary, has been obliterated across it.

Many roads remain much as they were in 1939. The extension of Highfield Road across the Cole was improved by the replacement of the humped bridge in 1986. Priory Road has been made as a dual carriageway almost to the Solihull boundary. A direct crossing from Walford Road to Stoney Lane over Stratford Road has been made, but the difficult intersections on Warwick Road cause increasing delays. On Coventry Road, where the third Swan went up (replaced by offices in the 1990s), the 1960s underpass is part of the racetrack that Coventry Road became in the early 1980s, as half of Hay Mills' shops were destroyed to make a multi-lane highway, punctuated with sets of traffic lights where drivers wait impatiently. Wherever radial and circular traffic meet - nearly always at the heaviest-parked areas, the shopping centres - congestion can last all day. Supermarkets have more recently been built, with much-needed parking space: the first was at Green Bank, Hall Green.

Hall Green also acquired a library, Technical College, and a Bilateral School in the 1960s. Six other new schools were built by the 1970s, notably the former Grammar and Bilateral Schools at Swanshurst, later combined and now apparently the biggest secondary school in Europe. A number of secondary schools in Sheldon provide for many children of Church End Quarter. Pitmaston school closed after periods as secondary and primary, and more recently Yardleys school moved away from its older sites to modern buildings amongst factories. The manor which was once a single Anglican parish is now shared by nearly 20, and there are now scores of places of worship of all denominations and religions. One of the newest Anglican churches is that of St. Peter's Hall Green (1964), prominent on the skyline from the west.

All of the cinemas have closed: two in Hall Green were replaced by supermarkets (Rialto and Robin Hood) one by a car showroom then furniture shop (Springfield), two others survive as a factory (Tyseley) and a Bingo ball (Atlas), while the demolished Tivoli gave its name to a huge multi-purpose development at the Swan junction, including flats, towers, and shops. The Adelphi at 'South Yardley' is a Sikh community centre, and the Warwick at Acocks Green is a bowling alley and laser-combat business. Hall Green Little Theatre at Fox Hollies is Yardley's first purpose-built example, an amateur achievement built on the site of a wartime water-tank (a number of church halls are of course equipped as theatres). The proliferation of filling-stations, car-sales firms, radio/TV shops, launderettes and betting-shops, were the most notable changes along the main roads, but filling-stations are now closing in alarming numbers. Large numbers of pubs, especially the larger inter-war roadhouses, have been razed for housing or other commercial use: this is probably the most surprising development of the years around the Millennium. Yardley Wood, for example, now has no pubs at all - the nearest, the Prince of Wales, is actually in Solihull. Perhaps the greatest architectural loss was the Good Companions on Coventry Road, which had fine art deco decoration. A notable and very welcome addition is the Fox Hollies Leisure Centre, with modern swimming pool and sports halls (1986).

There are four police stations in Yardley, at Billesley, Sparkhill, Acocks Green and Stechford, and two fire stations: Brook Lane, and Tyseley, which replaced Acocks Green's small station on Alexander Road in 1993. Nearly a dozen clinics for child welfare were conveniently situated throughout the District in the 1960s, but rationalisation has affected them and G.P. surgeries, so that they are now fewer and less convenient. The Women's Hospital closed in the 1990s, and has since been boarded up. Public transport was declining: there were 22 bus routes in the 1960s and some suburban train services from Stechford, Tyseley and Acocks Green, but Lea Hall Station was closed, and passenger services on the Stratford line were under threat for a long time. Bus deregulation has brought about something of a renaissance in public transport, and suburban rail appears to have a brighter future.

There are each year fewer relics of any century older than the nineteenth: 'the past around us' is coming increasingly to mean mainly mid-Victorian villas. Blakesley Hall, restored after wartime damage, and again around 1980 and from 1999-2002, is a very fine branch museum. Sarehole Mill was near ruin, but was saved for rural crafts and industry exhibitions and demonstrations of corn-grinding: it is Yardley's sole surviving working watermill. The only other working mill in the city is at New Hall, in Sutton. Restoration was completed in 1969: over 30 years later its connection with Tolkien is at last being fully exploited. In the same year Yardley village was declared a Conservation Area by the city, and through-traffic ceased in 1976, earning the village the designation 'Outstanding' from the Historic Buildings Council. However other buildings were not so lucky: for example the half-timbered Fieldgate Farm in Acocks Green, which was demolished despite protests in the late 1970s. Since the 1980s, however, there has been a new interest in archaeology and conservation. Bronze Age burnt mounds (probably prehistoric saunas) have been discovered in Fox Hollies Park. At the other end of the spectrum the Arts and Crafts environs of St. Agnes church were declared a Conservation Area, and in Hall Green School Road and Miall Road, together with the pub and shops, were declared a 1930s conservation area in 1988. The Coleside walkway is not only an amenity for walkers, but land management seeks to enhance the wildlife diversity as well. The fords in Hall Green have been bollarded to deter cars, and footbridges continue in use. Another former industrial site, now open to leisure use, is the Grand Union Canal. Towpaths, which used to be private industrial walkways, became overgrown and neglected after diesel engines superseded horses, but decades of pressure have finally resulted in new leisure uses not only for the water but also for the linear walkways that the towpaths provide.

Yardley's inhabitants have increased since the war far beyond the numbers who occupy new homes; it is impossible to estimate how many of the older and larger houses and some less ancient are in multi-occupation. The tenants of the usually inconvenient and ill-provided new flats included not only the ever-younger married couples of local origin, but incomers from overseas - Asians and West Indian in Sparkbrook, Acocks Green, Stechford and Hay Mills, and Irish in Sparkhill, where a powerful Catholic church and community were the attraction. From the 1970s onwards huge sums of public money were spent bringing the infrastructure of the inner-city suburbs back to a reasonable standard. Shops and places of worship sprang up to serve these communities, creating among other things a nationally famous Asian restaurant culture: the 'Balti Belt'. Since the 1980s, ethnic minority families and their Birmingham-born and bred children and grandchildren have been moving out from the inner-city suburbs into once homogenous areas like Hall Green. In the 1980s, in Hall Green and parts of Acocks Green, there were very high numbers of old people: the population is now becoming younger as well as more diverse as older residents have died or moved away into sheltered accommodation and families have taken their place. The pressure on existing communications and services is ever greater: in the last ten years the far-sighted road improvements made between the wars have finally been overwhelmed by traffic, and it is now the outer-city suburbs that need huge investment in remedial infrastructure works. These days Yardley must house and service people at a density one hundred times that of a century and a half ago.

In the 21st century, Yardley has no significance as a geographical or demographic unit: it has become submerged in the rest of the city, with workers and materials and products moving on wheels in all directions in ever-growing congestion. Its diversity of industry, shops, amenities, housing and people becomes greater every year. Its individuality was never great, and it was always affected by its awkward shape, its location across lines of communication and its nearness to Birmingham. The tiny village centre about the ancient church is not enough to sustain a sense of identity with the whole former Manor and Parish, especially as other less historic centres within the larger unit came to eclipse it in importance over a century ago.

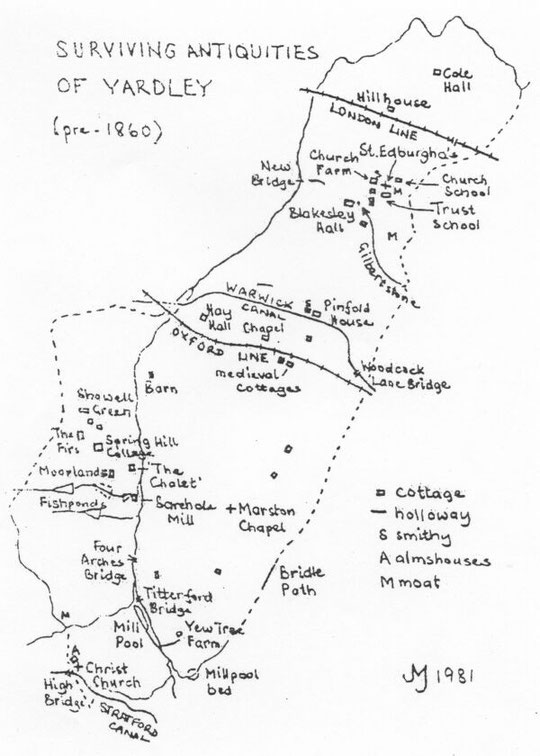

Surviving antiquities of Yardley, 1981

This map does not include the houses built in Acocks Green and elsewhere in the 1850s, for example on the Warwick Road.

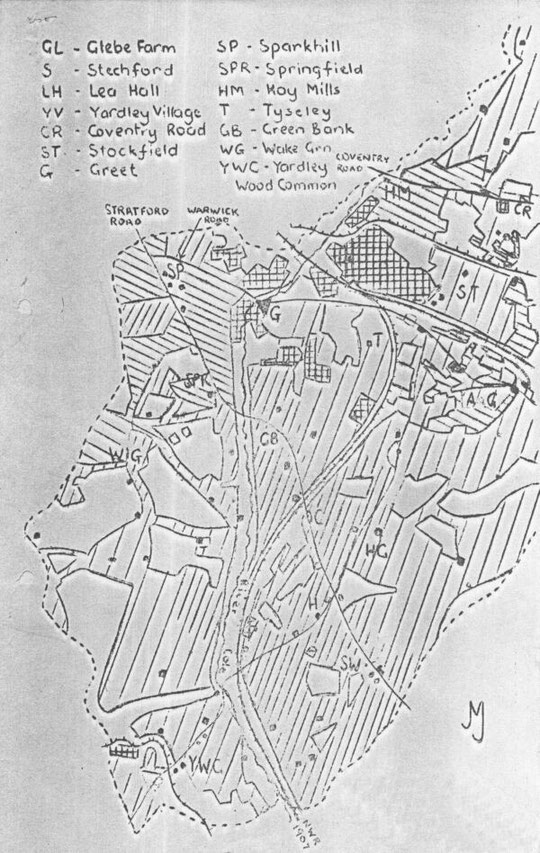

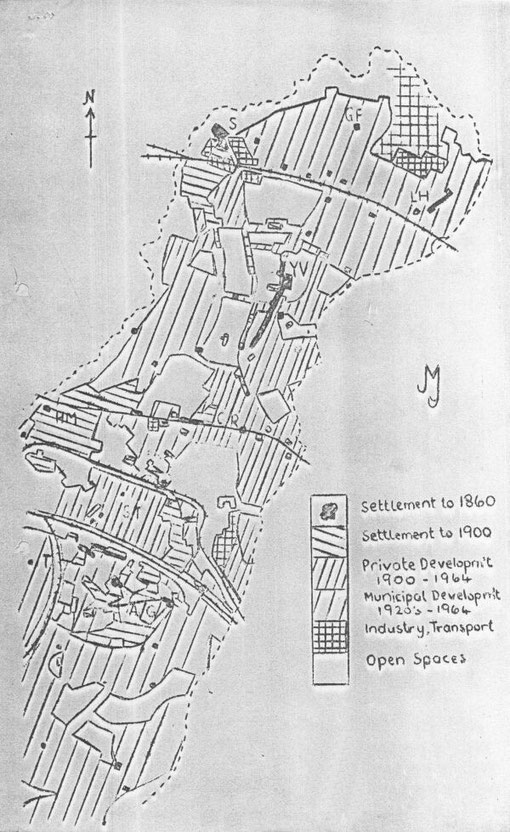

Urbanisation of Yardley (introduction)

The natural landscape

Ownership and administration

Yardley in medieval times (map)

Yardley at the end of the eighteenth century (map)

The early 19th century

The mid-nineteenth century

The Victorian half-century 1850-1900

The last years of independence

Development 1911-20

Two decades 1919-39

Yardley since the war

Urbanization maps

Surviving antiquities of Yardley (map, 1981)

Acocks Green History Society

Acocks Green History Society