Section five

Transgressions: Naughty, Naughty!!

Schools, by their nature, reflect all strands of society. The vast majority of children are quite content to conform to acceptable standards of honesty and behaviour but there are always a few who are not prepared to do so. The small minority of children who fall into that category might be doing so for a variety of reasons - attention seeking, boredom, sheer excitement or simply to acquire desirable objects that close friends already possess. Whatever the reason, or reasons, dishonesty and bad behaviour is a source of serious cause for concern and distress within a school.

Dolphin Lane’s first incidence of dishonesty occurred as early as October 1931.

‘Today an unheard of thing; money missing in two classes from teacher’s cupboards. Milk and Biscuit Money. …….. Sums of 10d and about 2/- respectively.’

Although the culprit was not immediately found, he was not so lucky when he tried to steal again four days later.

‘A boy named W.B. caught by Head Teacher attempting to obtain money from Miss Knight’s classroom during a period when this class was in the Hall. Boy owned up in the presence of his mother to having taken the sums referred to above. Mother expressed regret; made good deficiencies, at her own suggestion, by taking money from boy’s home money-box. Boy had a huge toy gun, which used up endless boxes of caps and most of money had been spent on purchase of the caps. Boy frequently attends pictures.’

No incidents of this nature, thought serious enough to record, occurred for another five years, then two boys from the school appeared in the Juvenile Court ‘for stealing torches etc.’ Both boys were fined 2/6d.

This punishment failed to prevent further incidents of a similar nature, three being recorded in a relatively short space of time.

In the first case two boys appeared at the Juvenile Court for stealing cigarettes. Sentencing was adjourned for twelve weeks and there was no record of the punishment given for this misdemeanour. The next two thefts each involved groups of three boys. In the first instance the boys were caught in the act of stealing 2/7d. Two of the culprits received twelve months probation while the other boy was fined 15/-. Toys were stolen in the other theft and all the boys involved were sentenced to six months probation by the Juvenile Court.

During the war years no thefts, either in the school or the local community, were recorded but in 1948 another pupil was before the Juvenile Court charged with shop breaking. His punishment was 12 months probation.

Further references of such anti-social behaviour were notable by their absence, so perhaps lessons had, at last, been learned.

Far less serious were the self confessed offences of some past pupils.

Gordon Parsons recalled … ‘I was caned on the hands by him (Mr Sutton) at least once - I can’t remember what for – and clearly remember how he would stand with the cane wavering above his head, seemingly building up force to bring it down. This was no doubt for effect but it certainly hurt.’

‘I wasn’t, I believe, a particularly naughty boy - despite the caning -

but I do remember in the Infants cutting off the plait of a little girl with cutting out scissors and being so frightened by the inevitable and understandable response from the teacher that I was relieved that my mother, who had just delivered me to school, saw me in distress through the corridor window and returned to find out what was going on. No doubt there were repercussions ... but I do not recall any specific punishment.’

John Bird also has a lasting memory of his lapse in behaviour –

‘On one occasion a boy called Bobby Weake and I were assigned to repairing the spines of books with gummed tape in the school library. We got a little bored with the work and when Mr Sutton happened to look in we were in a heap wrestling on the floor. Suffice to say we both had a firm rap of the cane on each hand.’

Bernard Rainbow also had his failings –

‘I was caned by Mr Sutton for throttling another boy. I didn’t dare tell my dad or I would have had another smack.’

Interestingly children were not the only miscreants; teachers and parents and others also ‘stepped out of line’ on occasions.

One teacher was accused by a parent – ‘of referring to her son’s appearance as Big Ears’ and just two days later the same teacher was accused by a different parent of ... ‘Criticising the dress of her daughter, calling her coatee that thing.’

Having received similar complaints from parents previously the teacher was informed these latest objections would be logged. Surprisingly there seemed to be no remorse about, or apology for, her actions as she responded by saying ‘I don’t want to see it.’ After a period of sickness and leave of absence to pursue an art qualification she moved to another school.

A final comment implied a certain amount of relief on the part of the Head Teacher -

There was no record of grossly unacceptable behaviour in the Infant School records but Miss Hood did note the following adult ‘misbehaviours’.

"Mrs S. came to school yesterday and was extremely violent and rude because her child Iris had been spoken to about coming to school in the afternoon without being washed."

"..when they (the school meals) on Wednesday the car was driven across the playground at a fast pace without an escort. The driver has bee told she must wait to be escorted up the playground where children are playing."

‘to be transferred… .. and her name removed from the staff of this school’

The Air Raid Shelter Saga: Keeping the Children Safe

By September 1938 the situation in Europe was serious and it was believed that events were ‘so fraught with possibilities of dreadful magnitude’ that notices of advice were sent to schools on such issues as air raid precautions, the distribution of gas masks and an emergency scheme for the evacuation of school children.

At the end of August the following year the international situation had become ‘most grave and evacuation of school children from certain areas of the city is to be proceeded with. This school is in … a Neutral Area and scholars are not in the evacuation scheme.’ Then on the 3rd September came the announcement that was dreaded ‘This day, Sunday, England is at war with Germany.’

The school was formally closed, except for organised games sessions in the playground, until mid October when all schools in Neutral Areas were told to re-open as soon as possible. Parents, however, had to be informed that -

‘1. No protection at school but protection will be provided as soon as possible.

2. Attendance at school will be entirely voluntary.’

Before a meeting with parents could be arranged the official Birmingham City Police circular ‘A.R.P. Rules for Schools’ were circulated as a matter of urgency. Its contents were discussed with an Inspector from Acocks Green Police Station, who suggested areas of the school that afforded some protection in the case of an emergency and also recommended the parents accept a ‘no dispersal of children policy.’

Approximately 160 parents attended the information meeting at which all the relevant issues were discussed and the ‘no dispersal’ policy, in the event of an air raid, was agreed. Parents were required to sign a form ‘accepting responsibility’ should the worse happen. The school re-opened on a voluntary basis the following day, the 17th October 1939, and two hundred and thirty-four children arrived for lessons.

The next week a stirrup pump, bomb bucket and scoop were delivered to the school and the caretaker and staff were given ‘a demonstration of its use.’ With so little protection for the children while they were at school action was urgently needed.

On the 25th October an architect surveyed the premises and suggested the construction of nine above ground shelters each of which would accommodate fifty children. It was pointed out that as the cover provided would only cater for four hundred and fifty children, the Infant and Junior Departments could not both meet at the same time.

Dissatisfaction with the proposed number of shelters was clear. If it was confirmed by the architects that there was insufficient space on the school site to increase the number of shelters it was suggested additional provision could be made available by either using the piece of waste ground opposite the school, by using tenant’s land adjoining the school or even by converting corridors and cloakrooms.

With no immediate promise of additional shelters it was agreed the Junior children should attend school from 9am to 1pm each day and the Infant children from 1.30pm to 4pm. Parents were asked to sign a form agreeing to the proposals and also consenting to the older children receiving homework each day. Only three hundred and fourteen homework forms (67% of the number on roll) were returned!!

While the shelters were under construction air raid drills, which involved moving to ‘refuge rooms and spaces’, were practiced and there were daily checks on all the children’s gas masks and identification tags. New gas mask boxes were provided as and when necessary. In the meantime every opportunity was taken to continue the campaign for more shelters than those agreed.

By the time the school closed for the Christmas holiday in 1939 the shelters were nearing completion but ‘wood for the interiors is difficult to obtain’. By mid January, however, an official notification was sent to the school stating the shelters were ready for use and that it was to open on ‘a compulsory basis.’

Parents were informed of the Education Department’s and three hundred and seventy-four of the four hundred and seventy-four children on roll at the time arrived for lessons. Of the hundred ‘missing’ children it was noted - ‘some of the absentees may be evacuated voluntarily or in other schools, and others for various reasons cannot at the moment be accounted for.’

The lack of sufficient protection for all the children was still a great concern to Mr Sutton and Miss Hood, who attended several meetings at the Education Office where they ‘pleaded for extra accommodation.’ Still there were no immediate promises but it was agreed the children could continue attend on a part time basis but their attendance was to be compulsory.

A number of concerns were raised about the shelters after the very first practice -

‘ 1. The shelters are not gas proof.

2. They are extremely cold and draughty especially in such weather, as we have recently experienced. (Vigorous exercises are, of course, not allowed).

3. There is no artificial lighting or heating.

4. The temporary W.C.'s are not screened.

The concerns were immediately forwarded to the Education Department, the letter adding … ‘I understand the above points are under consideration but I should be glad to have the foregoing disadvantages dealt with as soon as possible.’

Air raid practices were held twice weekly … ‘once by the class teacher and once by all school under supervision of Head Teacher.’ Each class was allocated a numbered shelter except the ‘top class’, which was distributed among the other classes. For obvious reasons the practices were taken very seriously and were expected to be carried out within the times agreed by the staff.

The lack of accommodation in the shelters was an ongoing concern and without any promises, even to the conversion of cloakrooms, an announcement in the Schools’ Bulletin concerning the dispersal of older children, prompted another letter to be sent to the Education Office stating … ‘I believe the provision of further Air Raid protection at this school is under consideration and I trust it will be found possible to provide further protection as soon as possible so that the question of partial dispersal will not arise.’

Both Head Teachers were again invited to the Education Office to discuss the provision of extra shelters and also to consider Miss Hood’s concern about the use of one shelter that she believed was too close to the Infant classrooms.

The badgering and persistence of Mr Sutton and Miss Hood eventually paid dividends because in June 1940 there good news at last … ‘Work to be commenced on a further five shelters for Air Raid Protection at this school.’

The 1939/40 school year had been demanding for everyone -

‘The school year ended has been one of extreme difficulty for the teachers for in their attempts to continue the education of the children they have always been confronted with possibilities and uncertainties concerning their physical well being ... it is hoped that as the five extra shelters are nearing completion the school may be opened during normal periods. By this means the children will have a place of refuge and security (so far as can be provided) for longer periods during the day.’

When the school re-opened on 12th August the necessary permission to use the new shelters had not been received so in a letter to the Education Office it was suggested ‘ the fitting of curtains and lamps would make their use possible.’

The very next night an air raid affected Acocks Green and very few children arrived for school the following day. Further raids over the weekend of 24th and 25th August demolished a house in Wildfell Road and damaged others nearby, but fortunately Mr Sutton was able to report,

‘none of our children are casualties.’

The original shelters were first used during a daytime air raid on the 4th September.

‘The children were quickly and orderly taken to the shelters. They of course, innocently perhaps, enjoyed the experience in the majority of cases. The Head Teacher visited each shelter during the period of warning and afterwards to inform teachers that ‘Raiders Passed’ signal had sounded and that children could return to the classrooms.’

Commenting on the Infant children’s reaction to the alarm Miss Hood noted:

"The children were very calm and went to the shelters in perfect order. No air raid took place."

Now more anxious than ever to have the new shelters available for use, arrangements were made for them to be inspected by an Education official. It was agreed …

‘two shelters, Nos.13 and 14, were very dark, especially on entry.’

Action concerning the speedy attention to lighting, the screening of W.C.s and provision of buckets was promised and it was suggested the shelters could, with the Head Teacher’s approval, be used and the full time attendance of the children be authorised.

The shelter situation was now looking more positive than for sometime but even before the official notification for full time opening arrived another problem had arisen –

‘ After a very wet weekend, the first for months, I have today discovered that there is some leakage in the shelters and that defective drainage allows water to accumulate in Shelters No.2 and No.3 especially.’

However these difficulties were not thought serious enough by the Education Department to prevent the school opening on a compulsory, full time basis and this was confirmed in a letter.

With the increased number of shelters it was necessary to re-allocate them between the two Departments. It was agreed eight would be for the sole use of the Junior children and six for the Infant children. As there were nine Junior classes it was still necessary for the oldest children to be dispersed and share with other classes.

From September 1940 through to July 1941 the children’s lessons were interrupted by daytime air raids on forty-seven occasions.

Some days two alerts were sounded while on one particular day there were three separate warnings. The length of time spent in the shelters varied considerably but it was rarely less than twenty minutes. On one occasion the children were taking cover for two hours.

Severe damage was caused during sustained bombing of the city during the night of Friday 22nd November 1940 and as a result Head Teachers were advised to ‘make immediate preparations for the evacuation of school children.’

When the problem of an unexploded bomb near the school had been resolved, arrangements for the evacuation of Dolphin Lane children began in earnest.

On his return to Birmingham, where he had been overseeing arrangements for children evacuated to Retford, Mr Sutton again turned his attention to the vexed question of the air raid shelters.

"The shelters are still to my mind unsatisfactory in some details. After much writing, personal calls, phone messages, improvements in dryness of shelters has been made but some are still unsatisfactory. The greatest defect is the darkness of Nos.12 & 13. The question of lighting has been referred to officers on a number of occasions.’

Despite their deficiencies, the shelters were used regularly during the daytime air raid warnings that continued through until July 1941 and even when the raids lapsed, the routine practices continued.

The last enforced use of the shelters was on the 4th March 1943 when …

With the end of the war, announced on the evening of 7th May 1945, the shelters had fulfilled their usefulness; the buildings that had been so eagerly fought for a few years earlier were now a hindrance. Numerous requests to the Education Department for their removal went unheeded so Mr Sutton turned to a local councillor for support but even this failed to bring the positive result he was hoping for.

The in May 1947, a letter was circulated to all schools by the Chief Education Officer informing them a child had drowned in a flooded air raid shelter and requesting an update of the condition of all shelters on individual school sites.

‘Just before school assembled and many children were in the playground an alert was sounded. In three minutes all children were in shelters. I was, however, concerned at the number of parents, who for the first time came to ask to take their children home. This was permitted. So far as I could ascertain the recent attacks on schools had caused worry.’

The shelters at Dolphin Lane presented little danger of flooding, but never one to miss an opportunity, Mr Sutton highlighted other disadvantages of leaving the structures in place in his reply.

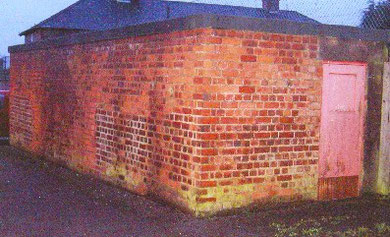

Despite his concerns there is no record of any immediate action being taken to remove the shelters. However, some were eventually demolished, some were incorporated into the school building and used for other purposes while others were left standing and are still in place today.

Some ex-pupils who used the shelters as children remember the experience.

‘I recall one daytime raid or threatened raid when we were shepherded into the brick and concrete shelter …. My mother, along with a few other mothers, turned up to take me home during what must have been the warning period. I can only assume that the thinking was that if the worst were to happen then the family would go together.’

Gordon Parsons

‘I remember us having to go into the brick shelters if the sirens went. You were not allowed to go home until the ‘all clear’ unless a parent fetched you. I hated gas masks. They made me feel sick and I cried every time I had to practice in class. I still have mine (don’t know why!).’

Brenda Dainty (nee Nicolle)

‘I recall the brick air-raid shelters being built at the front of the Junior school playground and thinking they didn’t seem as safe as the underground Anderson shelters we, and our neighbours, had in our gardens. They proved popular during games of hide and seek.’

John Bird

‘When I left School (1947) there were still brick built air-raid shelters around the main block. If you were very brave you would creep into the dark shelters to look.’

Margaret Weston (nee Millward)

‘… there was one shelter I remember that when it rained there was a big pool of water and I was paddling in it one day. Mr Sutton spotted me. He told me to report to his study, then I had two stokes of the cane on both hands while telling me that my mother could not afford to keep buying me boots.’

Evacuation: From Birmingham to the Countryside and Back Again

The evacuation of children from Birmingham began on 1st September 1939 but as Acocks Green was not one of the districts that the City Council believed to be most at risk from enemy attack any thoughts of evacuation from Dolphin Lane did not arise until late January 1940 when the school re-opened on a compulsory basis after a spell when the attendance for children was voluntary. As only three hundred and forty seven of the four hundred and forty seven children on roll arrived for lessons it was thought some children ‘may be evacuated voluntarily.’ In August 1940, when the school re-opened after the summer holiday, the lower numbers attending suggested ‘several children are still on private evacuation.’

In May 1940, as the international situation worsened, the Chief Education Officer sent a circular to schools, encouraging all teachers to volunteer for evacuation duty. Those unable to do so were requested to ‘write personal letters’ explaining why they were unable to offer their services.

On the 26th August 1940 the realities of war reached Acocks Green. During a German air raid several houses in Wildfell Road were demolished and others rendered others unsafe. None of the Dolphin Lane children were injured during the attack but parents in the area were seriously concerned about their children’s future welfare. It was not surprising therefore, that –

‘Children continue to leave the school for private evacuation to safer areas, as aerial activity has become more marked and many children are enquiring about evacuation overseas. So far 18 children are registered under the scheme.’

From the beginning of September 1940 air raid warnings, while the school was in session, occurred at regular intervals and lessons were repeatedly interrupted as children huddled in the shelters. The already uncertain situation worsened on the night of Friday 22nd November when a concentrated German raid on the city caused considerable damage.

The Education Committee decided it was time for action -

‘The Head Teacher was summoned by wireless to attend a meeting in the Technical School, Suffolk Street, at 10.30 am on Sunday 24th November.’

Alderman Byng Kenrick and Dr. P. Innes, the Chief Education Officer, addressed the meeting. The main points of information given were -

‘1. The whole of the City was an evacuation area.

2. The City had been divided into two main areas:-

-

- Waterless areas.

- Areas where water was still obtainable.

For various reasons evacuation from ‘waterless areas’ would start forthwith and Head Teachers were instructed to return to schools and make immediate preparation for the evacuation of school children. The returns were to be in the Education Office by Tuesday morning.’

That same afternoon, events took a turn for the worse at Dolphin Lane. Delayed action bombs had been dropped near school and many of the nearby houses had already been evacuated. As it was in the danger zone the school could not be used.

Arrangements were hurriedly made with Rev. Kelly of St. Mary’s Church, to allow the children and their parents to assemble at Bishop Westcott’s Church Hall, in Greenwood Avenue until the school could be reopened.

At a meeting held in the Hall on the afternoon of Monday 25th November, the parents were informed of the Education Authority’s latest decision –

‘We have been instructed to have children ready for immediate evacuation and they were to assemble morning and afternoon ready for departure.’

Dennis Simons

Not wishing to wait any longer to send their children to safety, or to split up their families, some parents chose to send their younger children with older siblings attending Hartfield Crescent School. Among these were Brenda Nicolle, aged 9. (4th left front row) and her sister Eunice, aged 12, (7th left second row with newspaper ‘fancy’ hat). They left for their destination, Loughborough, on the 27th November the day before Dolphin Lane was finally declared safe and the children could return to their classrooms, dressed and ready for immediate evacuation.

On the 29th November came the news that many anxious parents had been waiting for - children at the school would be leaving for evacuation the very next morning, Saturday 30th November.

At 8.30am one hundred and twenty children gathered at the school and travelled by bus to Castle Bromwich Railway Station, en route to East Retford, Nottinghamshire. Eighty-three of the children were from the Junior Department, twenty were from the Infant Department, eight were from Hartfield Crescent Senior Boys and nine were from Hartfield Crescent Senior Girls. The party was made up of mixed ages as members of individual families opted to travel together. There was also a separate group of approximately eighty children from the Infants Department, under the supervision of Miss Hood. In this combined party, leaving for a safer rural location, were Syd Bardell, Dorothy and June Powell, Joan and Evelyn Kempson, the Henbury family – Arthur, Brian, Alvis and Sheila and Hilda Penson.

When the Dolphin Lane children arrived at Castle Bromwich, they joined those from a number of other schools making up one large evacuation party. The overall total, approximately nine hundred, was made up of eight hundred children and a hundred adults, i.e. teachers and helpers.

The schools that making up the overall evacuation party were –

Dolphin Lane Junior, Dolphin Lane Infant, Alum Rock Junior, Acocks Green Senior Mixed, Acocks Green Junior, Acocks Green Infant, Hall Green Junior & Infant Stirchley Street Junior, St. Michael’s R.C., Nansen Road Junior & Infant, Nansen Road Senior Girls, Moseley C. of E., and Ingleton Road Junior.

The Dolphin Lane School party was supervised by -

Head Teacher - Mr. George A. Sutton; Chief Assistant - Mr. V. E. Perry

Assistants - Miss E. M. Jessop; Mrs G. Holder; Mrs N. Kent; Miss C. Folland;

Miss K. Callow; Miss F. A. Appleton; and Miss G. Bailey.

Helper - Miss M. Holder

Miss A. Davies, the Chief Assistant Mistress, remained at the school to answer enquiries and to maintain contact between parents and their children.

Mr Sutton reported -

‘I was put in charge of the party and after the kind of journey one would naturally expect under the circumstances, we arrived at Retford, Notts, at about 3.30 in the afternoon of Saturday 30th November 1940. The authorities had made provision at short notice to obtain billets and by 9 pm. most children had been housed.’

A substantial programme of organisation was necessary to ensure this temporary re-settlement of children was efficiently carried out. New Ration Cards and Identity Cards had to be provided, all children had to have a thorough medical and school places had to be allocated. In addition to these necessities, a scheme had to be established with Birmingham for the supply of clothing, boot repairs etc. and also a system set up for dealing with children who were unhappy in their ‘billets’.

After the first few days teachers and helpers who were no longer needed at Retford returned to Birmingham.

‘The full story of our settling in at Retford is far too complicated and lengthy to be chronicled here ... but the many difficulties were in the main cleared satisfactorily by the co-operation and understanding of the Retford Authority and the Birmingham teachers. I am permitted to say this, I think, because I was asked by the Authority of the Borough of Retford to act as officer-in-charge to the Birmingham party and as I return after a month at Retford I can honestly say that although there was plenty of work, the association I had with the Retford Authority from the Mayor to the teachers is a happy memory among tragic days. After all, to take eight hundred young children from their homes to foster parents far away from home can be tragic in many of its aspects but the kindness generally in the Reception Area soon brought rest and happiness to the many tired and weary children. The change from our last days in Birmingham to the serenity of Retford, and the visits of parents for a short re-union, soon established pleasant conditions of existence, which the children were not slow to appreciate.’

On 5th December, just days after the first evacuation party had left, Miss Davies was called to a meeting at which she was informed … ‘names could be taken for a further evacuation of children to take place on Tuesday 10th December 1940, to the rural areas under the Nottinghamshire County Council.’

Arrangements were made for Mr Sutton to meet Miss Callow, the teacher in charge of the nineteen children from Dolphin Lane and the ten pupils from Hartfield Crescent Senior Girls, near Retford. He wanted the new arrivals to join the children already at Retford but Dr MacMahon, the Birmingham Schools’ Adviser in over-all charge of this latest group of evacuees, insisted they went on to the rural areas of North and South Leverton as planned.

On the night of 11th/12th December considerable damage was caused to Dolphin Lane School when an A.A. shell struck the roof. In spite of this Mr Sutton decided to remain in Retford believing that the need to improve communications between Birmingham and the Education Authority at Retford, particularly on money matters affecting the welfare of the evacuated children and their teachers, was more important.

The summary of a meeting between Mr Sutton and Dr MacMahon and a representative of Retford’s Education Office, during which there was a review of staffing, the payment of teachers’ salaries, classes, stock, housing, the health of the children, general supervision and arrangements for Christmas, was taken by them to Birmingham for discussion with a representative of the Education Authority. Mr Sutton was surprised that the Birmingham officer receiving the report was far more concerned about the damage to the school than he was about the evacuated children and

‘suggested that I should stay in Birmingham, although there were urgent matters I had left uncompleted’

Many of the concerns, he was informed, were outside his province although he believed

‘ as I was accepted at Retford as the representative of Birmingham all these matters had been left in my charge.’

He reluctantly accepted he should remain in Birmingham but the arrival of the next teachers’ salary warrants, including those for the teachers on evacuation duty, gave him a reason to return to Retford. As ‘Head Teachers, or teachers-in-charge, were authorised to ‘negotiate’ the salary warrants Mr Sutton decided to cash them and take them to Retford ‘to hand over the amounts, which the young teachers especially, were no doubt anxious to receive. They had gone away hurriedly and board, lodging etc. needed attention.’

At a meeting with the Evacuation Office at Retford arrangements were made for his teachers to be given their salaries. They ‘received with thanks, and enthusiasm, their salary in hard cash. It is to my entire satisfaction that they were the only teachers at Retford to do so.’

Teachers from other schools were not as fortunate and there was some dissatisfaction that their Head Teachers had not made similar provision.

Before leaving Retford on that occasion, Mr Sutton handed over his duties to the Head Teacher of Acocks Green Senior Mixed School and was able to inform him that the Mayor of Retford ‘was likely to provide 1/3d per head for Birmingham children’ towards their Christmas festivities. It was left to the teachers of the various schools remaining on evacuation duty, to make arrangements among themselves for their holidays at Christmas and the New Year.

It was not too long before yet another evacuation party was bound for Retford and once again Mr Sutton was ‘given the job of teacher i/c of all schools.’ On March 3rd 1941 approximately four hundred children left Castle Bromwich, but of these only seven were children from Dolphin Lane School. The ‘journey was without any untoward event’ and as Mr Perry, Miss Folland, Miss Callow, Mrs Kent and Miss Bailey were still on duty with the remainder of the group that left the school on the November 30th, no further input was needed from Mr Sutton.

Although by mid August 1941 ‘numbers of children have returned from evacuation’, moving children to safer areas had not yet come to an end. On 21st November the school was notified a further evacuation was planned for the first week of December, the destination being Bargoed, in South Wales. Only six children from Dolphin Lane were in the party of sixty-two children brought together from twenty different schools. The whole group, again entrusted to the supervision of Mr Sutton, went by bus to Tyseley Station and then by rail to their destination.

‘Everyone arrived safely and all the

children were in their billets by nightfall.’

The teachers, however, were not so fortunate as no provision had been made for them. Luckily, a local doctor came to their rescue and provided some of them with hospitality while other suitable accommodation was organised.

During 1942 the teachers on evacuation duty at Retford, Leverton and Bargoed returned to the school when their services were no longer required. Likewise there was a steady drift of children back from their temporary homes in the country to their own families in Acocks Green.

The memories of the past-pupils, evacuated as children, range from total loathing to fun and happiness.

‘We went on a coach to the station. The train had a blue streamlined engine. We took our gas masks and a case with clothes in it. When we got there we sat on benches in a hall waiting to be chosen – a bit like a cattle market. Mr and Mrs Fletcher chose me, with another boy, but he soon went to live somewhere else. It was a cold winter. We were often chased and ‘duffed’ up by the local children. I was not happy there.’

Sydney Bardell

Mr and Mrs Leeming chose my sister and me. They made us take all our clothes off and sit under a ray lamp. We hated it. We were only there for a week.

Dorothy Bromage (nee Powell)

‘I was evacuated to relatives in Worcestershire. Evacuation for my sister and I was easier than for many children as we were able to be placed with relatives’

John Bird

‘I remember being shepherded into a school - house where we were allocated accommodation. Luckily I was with my brother and my sisters were next door. We had to fend very much for ourselves as our widow woman, Mrs Hall, we were led to believe, was a lady of the night.’

Brian Henbury

‘My sister and me were evacuated to Retford. I remember us waiting outside the school with labels pinned to our coats and a few possessions. We were taken to Acocks Green Rail Station. On arriving at Retford we were dropped off at St. Saviour’s Church Hall to await families who would take us in. Because we would not be parted we had to wait until someone would take us both. Eventually a young boy came in and said his auntie Annie would take us. Mrs Palmer’s husband was working nights at the Gas Works so we did not meet him until the next day. He was very nice and made us welcome. …… We had a happy time in Retford apart from the time Evelyn fell into the river while playing ….’

Joan Sparrow (nee Kempson)

Section one

Introduction – Goodbye Green Fields and Country Lanes

Getting Started

Buildings – Meeting the Changing Needs

The School Staff – Comings and Goings

A Broader Education – Talks, Festivals and Visits

Concerts and Performances – A Chance to Show Off

Christmas Celebrations

Royal Occasions – Visits and Celebration Holidays

Physical Activities – Athletics, P.T. and Games

Fund Raising – Helping Others and Supporting Ourselves

Medical Matters – The Doctor, The Dentist and the ‘Nit’ Nurse

Accidents and Misfortunes – Cuts, Bruises and Even Worse

Transgressions – Naughty, Naughty!!

The Air Raid Shelter Saga – Keeping the Children Safe

Evacuation – From Birmingham to the Countryside and Back

Appendix 1 Birmingham Educational Districts & School Lists

Appendix 2 New Pupils’ Previous Named Schools

Appendix 3 Sketch Map of the Local Roads Housing Dolphin Lane Pupils

Appendix 4 Memories – Dennis Simons

Acocks Green History Society

Acocks Green History Society